By Scott Stuewe, DirectTrust President and CEO

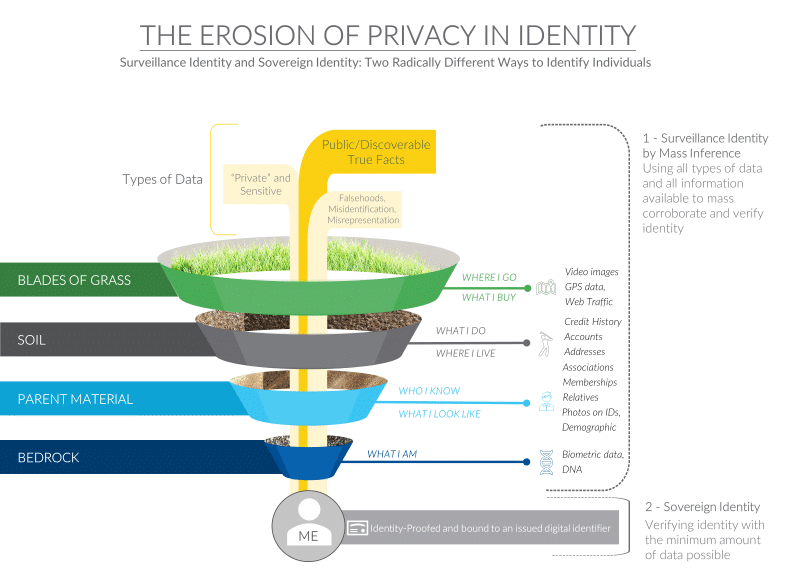

As data about individuals becomes more readily discoverable, we need to take care not to allow the erosion of our privacy as we look to tackle identity and establish trust on the internet. As we create tools to identify people for the right reasons, we need to remain vigilant that we don’t lose control of all our personally identifiable information in the process. “Trust-in-identity” is one approach to identity resolution while identity “surveillance” is another.

Regardless the method used to identity-proof an individual, the information used to conduct identity-proofing is itself personally identifiable information (PII). (If you missed my blog on identity-proofing, check it out here). The picture of a driver’s license, a video of your likeness, the driver’s license number – if any of this data become compromised or available on the dark web their value as identity-evidence is degraded and the risk of fraud increases. The value of any remaining anonymity is lost.

Even biometrics, including genomic data, are just data points which can be stolen. They uniquely identify individuals extremely accurately, but if they are compromised, they could become the new “mother’s maiden name” – once something is discoverable it can be used in fraud or misrepresentation. This is analogous to overusing antibiotics that lose effectiveness when they are used inappropriately. There are certainly ways of safeguarding this data, but such means must be used effectively so biometrics themselves don’t become a target of identity theft.

Registration authorities generally utilize extremely secure mechanisms to store the attributes about people used as identity evidence in the process of proofing. Mostly today this verification does not include biometrics, it’s usually limited to evidence used to proof “biographic” information.

Looking at the galaxy of true facts which can be used to identify individuals and their increasing availability, there are two conclusions one can come to. The “trust-in-identity” perspective is that only digital identifiers which are issued and bound to trusted and effective identity-proofing processes are secure and durable. Such identifiers can be revoked like a credit card if they become compromised.

Looking at the galaxy of true facts which can be used to identify individuals and their increasing availability, there are two conclusions one can come to. The “trust-in-identity” perspective is that only digital identifiers which are issued and bound to trusted and effective identity-proofing processes are secure and durable. Such identifiers can be revoked like a credit card if they become compromised.

As a part of the “bedrock” section in our diagram, your biometrics aren’t really your identity, they are just data you should try to safeguard. There is no changing your face after you have posted hundreds of pictures to Facebook, or your genome if your 23AndMe test results get out.

Moving up a layer, you can’t change your relatives if you have an Ancestry.com profile, and you don’t want to move out of your home to protect your identity – your address is easily found in real estate records.

Identity-proofing uses the minimum necessary evidence and trusted identity providers to issue a digital authenticator – cryptographic material that is bound to the proofed identity of the individual. Whether on a “smart card” or in a smart phone or some other portability approach, this is undeniably the safest way to provide a credential to gain access to sensitive information or capabilities. This is done without divulging personally identifiable information in the process of “transacting”. DirectTrust Accredited Authorities issue such digital identifiers for use to ensure trust in identity for secure health information exchange today (see my prior blogpost to understand how).

The alternative conclusion (and one increasingly arrived at) is that as more data about you is public it becomes much easier to identify you without your consent. Most would call this approach “surveillance”. This gets really good when the “blades of grass” information is linked with more reliable data from the lower levels which are also readily available. This data might be based upon true facts about you, but it could also be in part based upon falsehoods and mistaken identity.

Whether this is concerning depends upon what use will be made of these “inferences”. Somewhat benign surveillance enables personalized behavior and targeted assistance when a repeat customer is on a website. They don’t necessarily know you, but they know you have been here before. “Cookies” make this possible. It can be a bit creepy when they target advertisements based on your browsing behavior. When you create an account on their website, they can link the data on your habits with who you are (or who you claim to be).

Contributing to the potential of surveillance as an approach are the credit-bureaus who initially collected data (reported by creditors) for the purposes of determining the credit worthiness of consumers. As a result of The Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act (FACTA) legislation from 2004, we have seen increased transparency into credit bureau data in the form of free access to credit reports. Prior to FACTA, consumers had to pay to view their credit scores. This capability allows consumers to monitor inaccuracies and inappropriate use of their identity including the opening of new accounts without their knowledge. Transparency is good.

The concentration of this credit data is a tempting target for identity theft – witness the Equifax Data breach that put an end to the use of Knowledge Based Authentication (or KBA) for identity-proofing as described in my last post. Breach is bad.

These same companies have started businesses selling “identity protection” service to consumers, effectively selling the surveillance data back to them. More concerning are cooperative agreements (like the one between Equifax and Neustar) making services like “Asset-Based Customer Segmentation for Financial Services” possible. This allows the use of credit data from “deep in the soil” and other “blades of grass” data available on the web to determine what part of the population to target for financial products “based on estimated measures of consumer financial capacity, investment style, behaviors, and characteristics.” Similar products that rely on re-aggregated data are sold to law enforcement to enable a “known associates” search used even in the case of routine traffic stops. If you’re like me, you may find this fact surprising and troubling.

Once individually identifiable data of different types is aggregated there is little to limit the ways in which such data can be used and monetized.

You probably allowed this broad use of your credit data when you signed your credit card application. It’s not illegal, but it is scary. Data collected for one purpose and used for another is suspect. Looking at our graphic you can see that the data that is collected by the credit bureaus married with the data available on the web can provide an extremely accurate picture of who you are.

Given the ubiquitous nature of cell phones, there are numerous approaches to utilizing them as tools for surveillance. Governments around the world and society in general are trying to determine the risks and benefits that might result from using identifiable data like cellphone location information or schemes that use Bluetooth to identify individuals that have been in contact with COVID-19 infected persons. The enhancement to both iOS and Android phone operating systems launched as a collaboration between Apple and Google is said to be “privacy preserving” and is definitely less concerning than utilizing cellphone location data and the even more invasive approaches used in many countries including China, Iran, and Israel. Even the ACLU has noted that the Bluetooth model is perhaps the most acceptable approach, but offered guidance that “any contact tracing app remains voluntary and decentralized, and used only for public health purposes and only for the duration of this pandemic.”

The ability to re-identify individual attributes of a person gets pretty easy if you combine data from different sources. A fascinating example was an article that showed that “it took only minutes – with assistance from publicly available information — for us to deanonymize location data and track the whereabouts of President Trump.” Other articles showed that employees from the Pentagon could be reliably identified by seeing which addresses their location data showed that they traveled between.

The only data released to public health officials in the Apple/Google Bluetooth model will come from the individuals themselves that download an app. The native capabilities of the operating system (offered in second phase of the new model’s rollout) will let a user know when and where they have come in contact infected people but will share this data with no one initially. There is some question if the “app” approach will be effective since a similar app in use in Singapore was not in wide use – “only 12% of Singaporeans downloaded it”. This kind of data is personally identifiable health data, even though it was not collected by a health provider acting as a HIPAA covered entity. Some are concerned about the privacy implications of allowing this data to be aggregated with other social and/or health data. Clearly, deanonymization is easier when different data sets are married.

The Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR) whose job it is to interpret and enforce HIPAA are very conservative about easing restrictions that might lead to the erosion of the privacy and security protections that would apply to provider organizations that share data. Just this spring, the OCR hosted a webinar that described the previously announced “enforcement discretion” that modestly eases some restrictions relative to security and privacy in the COVID-19 Pandemic (slides here). HIPAA provides for “disclosures for secondary purposes” to public health. State laws vary in terms of what they allow in this regard. For now, OCR held the line on the “minimum necessary standard” which says that public health disclosures should be limited to just what is required for the purpose.

As different types of data (public health data, complete medical records, social data, credit data), even if they are deidentified, are aggregated whether by governments or by businesses, the ability to identify individuals by “inference” becomes extremely accurate and privacy is eroded in the process.

Both a “trust” approach and a “surveillance” approach to identity resolution will “work” and both will require additional infrastructure to enable them at scale. In which of these approaches should our society invest and place our faith?

We will need to carefully consider what we do in desperation in a time of crisis – the decisions we make about identity and anonymity are permanent. Infrastructure and policy in support of trust is a good investment.

This is part of a series of posts examining Trust-In-Identity. Join us for the next installment where we tease apart the difference between patient matching and identity.